The 1940s - Part 2 - Texas Star's KTHT

During World War II, the FCC refused to issue any construction permits or even hold hearings on applications for new radio stations unless the applicants had the equipment on hand to start construction. Roy Hofheinz had been disappointed in 1941 when his initial application for a permit for KTHT had been denied because of the equipment policy, despite a favorable recommendation from an FCC Examiner. Two of his partners had been more disappointed and wanted out so Hofheinz had taken a 75% interest in Texas Star Broadcasting. While the two other applicants did nothing, waiting for an approval before acting, Hofheinz rented a warehouse near Buffalo Bayou and began stockpiling equipment, both new and used, learning all he could about engineering and radio station operations along the way by consulting with others. Despite wartime restrictions on strategic materials, he finally managed to accumulate everything he needed and he petitioned the Commission to re-open the hearing. One of the other competing applicants was the Houston Press, owned by Scripps-Howard, which wanted a radio station in Houston.

During his earlier visits to Washington as early as 1939, Hofheinz had become acquainted with W. Ervin “Red” James, an FCC commissioner. They would become like brothers and James would be indispensable to Hofheinz in the approval process. James told Hofheinz’ (and later his biographer Edgar Ray) that after the initial hearing in 1941, FCC Chairman Leonard Fly had called him aside and told him he was not helping himself in Washington by being seen with Hofheinz because ‘he’s not going to get a radio station.’ Hofheinz had powerful political enemies in Houston who happened to own radio stations of their own and they did not want the competition, particularly from Hofheinz.

As the hearings resumed in May, 1944, Fly personally examined and cross-examined Hofheinz. who acted as his own attorney, making much of his failure to resign as county judge when he put in his application. Hofheinz had actually promised to resign as soon as the permit was granted, not before, and would not run for political office again, but he left the first day of the hearings convinced that Fly was going to succeed in blocking his application. Hofheinz was not a wealthy man and he had sold everything he owned to finance his dream of owning a radio station. He called his wife at home and told her it was all over, everything was lost and he’d have to find something else to do. His remaining partner, Dick Hooper, son of the man who developed the Doctor Hooper oil fields at Conroe and on the board of First City National Bank, promised Hofheinz he was good for the cash if they decided to appeal the expected ruling to the courts.

Red James was no longer on the Commission, having resigned to enter the Navy, but before leaving he had prepped Hofheinz on what to expect. Unbeknownst to Hofheinz and Hooper he had also briefed another Commissioner, Cliff Durr, a Rhodes scholar, on Hofheinz’s accomplishments and achievements. After Fly finished examining Hofheinz on the second day of the hearings, he opened the process up to the other commissioners and Durr said that he had a few questions of his own. Over the next 2 days Durr proceeded to lead Hofheinz through a recitation of his accomplishments, his reputation for honesty and integrity, his own powerful and influential backers, and so on. According to Ray, by the end of the hearing Fly would have made a complete fool of himself by voting against the application and Texas Star’s application was officially approved on May 23, 1944.

Days later Hofheinz was shocked to read a news story out of Washington that Chairman Fly had said the Houston hearing might be re-opened since the Judge had not resigned his post. Actually, days before the permit was granted, Hofheinz, worried about the future security of his family, had quietly filed for another term as County Judge. In early July Hofheinz was called before the Commission to explain why he had not informed them of this fact and had not resigned; the primary election was set for Saturday, July 15. Hofheinz had been County judge since 1936 and he told the Commission he believed his political enemies and potential competitors were going to block his application and he had no choice but to run again. Hofheinz told the Commission his competition was a monopoly, with all the stations on the air in Houston at that time controlled by Jesse Jones interests.

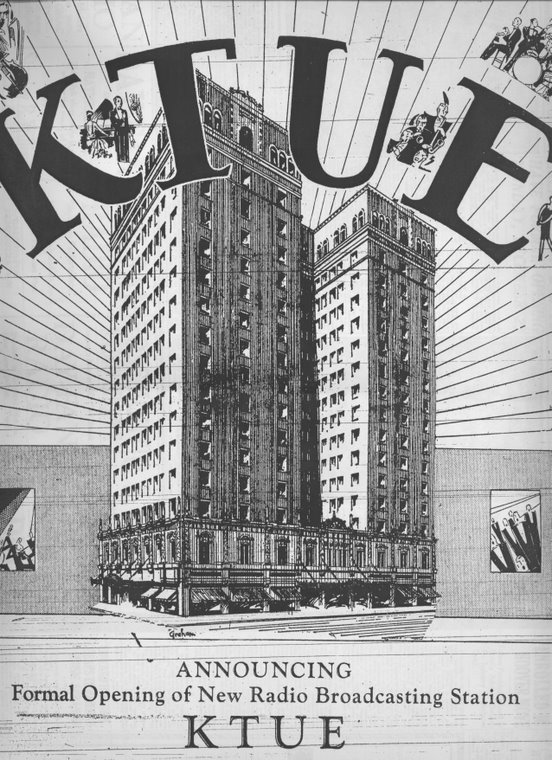

Hofheinz was sure his political enemies at home had informed the Commission of his last minute filing for re-election but assured the commissioners he would withdraw from the race once the go-ahead was given, that he would like to stay on in office to finish some projects but would step down immediately if the Commission so ordered. Returning to Houston Thursday, July 13, with the Commission’s blessing, Hofheinz told reporters at the airport KTHT would start test broadcasts from 8:30 to 12 Midnight that evening, then would continue with test programs from 6am to Midnight daily until final FCC approval. With no more fanfare than that, KTHT began broadcasting from studios in the Southern Standard Building at 711 Main.

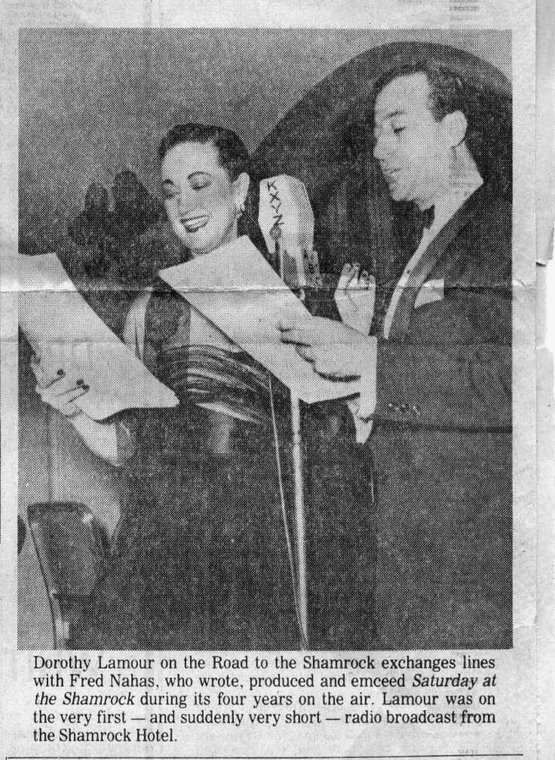

The schedule first appeared in the Chronicle on July 20th. The line-up of Houston stations as printed by the Chronicle that day included

KTRH, 405.4 Meters, 740 Kilocycles

KTHT, 243.9 Meters, 1230 Kilocycles

KPRC, 315.6 Meters, 950 Kilocycles

KXYZ, 232.4 Meters, 1320 Kilocycles

Though the government had started using kilocycles as the term to designate radio station’s frequencies in 1923, the Houston papers were still printing the corresponding meter designations, possibly for readers with very old receivers.

Though Hofheinz had filed for County Judge he had not run much of a campaign for re-election and according to family members and associates his heart wasn’t in it. He was defeated by a narrow margin in the Democratic Primary, which was tantamount to the election in those days, his first political defeat ever. He submitted his resignation to Commissioner’s Court but the Commissioners refused to accept it, saying they needed his leadership and guidance on several ongoing projects, and he served until the end of his elected term, in January, 1945.

In addition to the above account of the Commission hearings, biographer Ray presents also the viewpoint of Jack Howard, President of Scripps-Howard, which owned the Houston Press, a competing applicant for the permit on 1230 kc. Howard and Jim Hanrahan had their names on the Press’s application and had been present at the initial hearing in 1941, but both had gone off to war. Hanrahan was serving with the Army in Italy and Howard was with the Navy in the Pacific. The notice from the FCC that the Houston hearing was being reactivated was forwarded to Howard and he received it 8 months later. According to Howard, Hofheinz got the permit by default.

Howard’s account also gives insight into Hofheinz’s strategy before the Commission. Always acting as his own attorney rather than hiring an expensive Washington law firm, Hofheinz would show up at the hearings wearing a ‘pint-sized Stetson, lugging a bulging, richly-embossed Mexican leather briefcase, and breathless.’ His act, Howard said, was a most effective one, he came on as the simple little old country boy against the rich corporation. He then could proceed to astonish the Commission with his knowledge of law and broadcasting.

KTHT was the first new station in Houston since 1930. According to Ray, the call letters stood for ‘Keep Talking Houston Texas’ and ‘Kome to Houston Texas.’ The station remained at 1230 kc until 1948 when KNUZ signed on, taking over the 1230 kc frequency while KTHT moved to 790 kc and increased power to 5000 watts. Hofheinz was to sell a 75% interest in the station to Texas Radio in 1953 and then completely dispose of his interests in June, 1958. Robert D. Strauss was president of Texas Radio. Hofheinz was also part owner of Houston Consolidated Television, the group that put Channel 13, KTRK-TV, on the air in 1954, and Texas Star Broadcsting also operated radio stations in San Antonio and the Rio Grande Valley and had applications for 50,000 watt stations in Dallas and New Orleans, both of which had to be withdrawn due to cash flow problems.

KTHT became a 24 hour a day operation on October 1st, 1946, the first time since before the war Houston had had a 24 hour a day radio station. It was known as Demand Radio 79 and Downbeat in the late 50s and early 60s; subsequent call letters have included KULF ca. 1970, KKBQ-AM, ca. 1982, and currently KBME. It is now a sports station, the Sports Animal, and the original call letters are now used on Country Legends, 97.1.

Later in the 1940s Hofheinz formed Pilot Broadcasting with millionaire mortgage banker Thomas N. Beach of Birmingham, Alabama. Beach had put WTNB on the air in Birmingham in 1946 but did not understand radio. His searches for someone to help him run the station led him to Hofheinz, recommended as a man with a magic touch when it came to radio. When Beach tired of radio, Hofheinz and another Birmingham businessman, George Mattison, bought him out and took over the station which they changed to WILD. During his visits to Birmingham, Hofheinz met a young announcer at the station by the name of Loel Passe whom he brought back to Houston to work at KTHT. Passe was to go on to a long career in Houston radio and is remembered fondly as a play-by-play announcer for the Houston Buffs, Colt 45s and Astros.

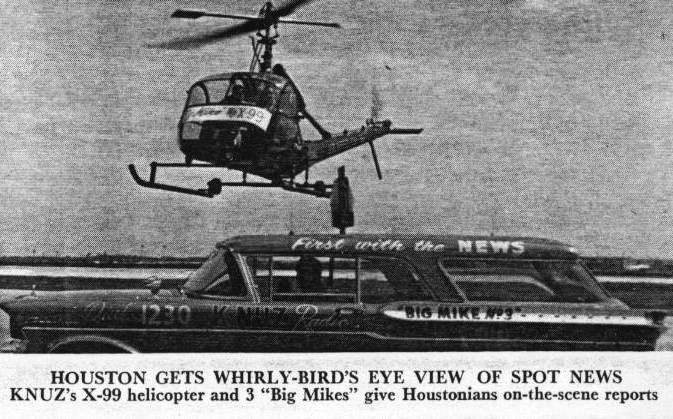

KTHT affiliated with the Mutual Broadcasting System. Ted Hills, who had been the operator and program director of KFVI in the mid-20s and KTLC later was hired as program director but Ray says there was never any doubt Roy Hofheinz called all the shots. The station intended to provide music and community involvement and emphasize live, on-the-scene news coverage and over the next several years history was to hand Hofheinz several sterling opportunities to demonstrate the latter commitment and the station was to receive praise and commendation for doing so. Hofheinz vowed the station would be profitable from the start and it was. He possessed not only knowledge of the law and broadcasting, but he understood programming, promotion and sales, and was able to give his sales staff the promotions they needed to attract advertisers. The first commercial on the station was on behalf of a restaurant in the basement of the Foley’s department store that just happened to be owned by Hofheinz’s father-in-law.

It wasn’t long after getting KTHT on the air that Hofheinz realized he’d made a mistake in going for a low-power outlet and he began making plans to move the station to a better frequency and boost power. Concerned that his political enemies and business rivals might take over the abandoned frequency when that day came, he confided his plans to some associates and advised them to be ready to file for the frequency as soon as he announced his application to move. That group of friends was eventually to win approval to take over the 1230 frequency.

There will be much more about KTHT on this blog, including special features on the use of the first wire recorder, coverage of the United Nations organizational meetings in San Francisco in the Spring of 1945, the Cruising Radio Studio, coverage of a devastating hurricane of August, 1946, and a public service project called the GI House, which will appear on the side-bar under the Stations category.

Note: The above account owes much to Edgar Ray’s biography of Hofheinz, The Grand Huckster, which includes background information not available in local news reports. But Ray is careless with details like dates and his account has been verified and supplemented wherever possible with local news stories.

3 comments:

It is such a joy to know that an

accomplishment of my Dad's is being

honored here. Few know of his love for the media- both radio- and television. One of his first jobs as a struggling kid at 16 while providing for his widowed Mother, was as a midnight DJ.He vowed he'd own a station someday. He is mostly known for having been County Judge at 24 and Mayor by 40: Most widely recognized as Father of The Astrodome and owner of the Colt 45/Astros.From Radio he ventured into Television as 16% owner of KTRK.Thank you for acknowleding him on your great site.He and my Mom, Dene I, were a winning team FOR

HOUSTON!*****

Dene Hofheinz Anton

(songwriter) got it honestly LOL

Thank you so much for your comment; I'm so glad to hear from you.

As I've remarked elsewhere on this blog, your Dad was certainly one of the most impressive figures to emerge in my study of the history of broadcasting in Houston and it is a shame his role has been forgotten. Somehow I knew before I started this that he had owned a station in San Antonio but I was so surprised to learn of all his accomplishments in the field and I wish both that he had stayed in broadcasting and I had had a chance to work for him.

He deserves to be in the Texas Radio Hall of Fame (as do several others in the history of the development of the media here in Houston who have been overlooked).

I have more to publish about KTHT coming up soon.

I was proud to be a part of KTHT in 1967 thru early 1968. Hired by Bill Bossi, worked with Ric Libby, Dee Wooten, Dick Sims, Jim Guidry (Jim Wilson) and helped Hal McClain get on the air there after he did a brief vacation fill-in. It was a very good station and I learned much from those I worked with. I saw many photos of the old studios and transmitter site, the studios were built more like a TV station than radio - audience theater, etc. Transmitter site photos very impressive!

Post a Comment